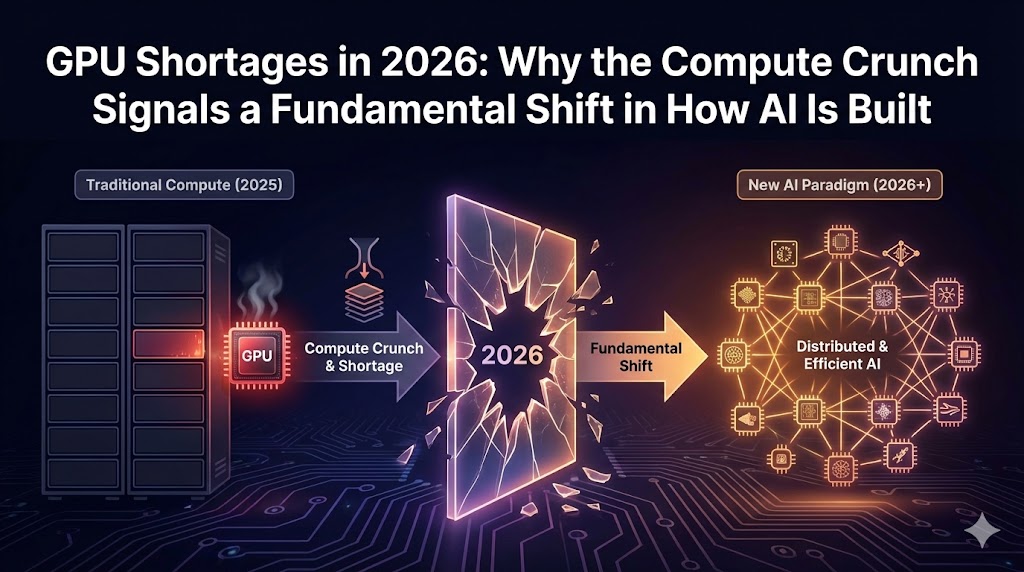

Question – What is driving the 2026 GPU shortage and how is it reshaping AI development?

Answer: The current compute crunch is a product of explosive demand from AI workloads, limited supplies of high‑bandwidth memory, and tight advanced packaging capacity.

Researchers note that lead times for data‑center GPUs now run from 36 to 52 weeks, and that memory suppliers are prioritizing high‑margin AI chips over consumer products. As a result, gaming GPU production has slowed and data‑center buyers dominate the global supply of DRAM and HBM. This article argues that the GPU shortage is not a temporary blip but a signal that AI builders must design for constrained compute, adopt efficient algorithms, and embrace heterogeneous hardware and multi‑cloud strategies.

At first glance, the GPU shortages of 2026 seem like a repeat of previous boom‑and‑bust cycles—spikes driven by cryptocurrency miners or bot‑driven scalping. But deeper investigation reveals a structural shift: artificial intelligence has become the dominant consumer of computing hardware. Large‑language models and generative AI systems now feed on tokens at a rate that has increased roughly fifty‑fold in just a few years. To satisfy this hunger for compute, hyperscalers have signed multi‑year contracts for the entire output of some memory fabs, reportedly locking up 40 % of global DRAM supply. Meanwhile, the semiconductor industry’s ability to expand supply is limited by bottlenecks in extreme ultraviolet lithography, high‑bandwidth memory (HBM) production, and advanced 2.5‑D packaging.

The result is a paradox: despite record investments in chip manufacturing and new foundries breaking ground around the world, AI companies face a multiyear lag between demand and supply. Datacenter GPUs, like Nvidia’s H100 and AMD’s MI250, now have lead times of nine months to a year, while workstation cards wait twelve to twenty weeks. Memory modules and CoWoS (chip‑on‑wafer‑on‑substrate) packaging remain so scarce that PC vendors in Japan stopped taking orders for high‑end desktops. This shortage is not just about chips; it is about how the architecture of AI systems is evolving, how companies design their infrastructure, and how nations plan their industrial policies.

In this article we explore the present state of the GPU and memory shortage, the root causes that drive it, its impact on AI companies, the emerging solutions to cope with constrained compute, and the socio‑economic implications. We then look ahead to future trends and consider what to expect as the industry adapts to a world of limited compute. Throughout the article we will highlight insights from researchers, analysts, and practitioners, and offer suggestions for how Clarifai’s products can help organizations navigate this landscape.

By 2026 the compute crunch has moved from anecdotal complaints on developer forums to a global economic issue. Data‑center GPUs are effectively sold out for months, with lead times stretching between thirty‑six and fifty‑two weeks. These long waits are not confined to a single vendor or product; they span across Nvidia, AMD and even boutique AI chip makers. Workstation GPUs, which once could be purchased off the shelf, now require twelve to twenty weeks of patience.

At the consumer level, the situation is different but still tight. Rumors of gaming GPU production cuts surfaced as early as 2025. Memory manufacturers, prioritizing high‑margin data‑center HBM sales, have reduced shipments of GDDR6 and GDDR7 modules used in gaming cards. The shift has had a ripple effect: DDR5 memory kits that cost around $90 in 2025 now cost $240 or more, and lead times for standard DRAM extended from eight to ten weeks to over twenty weeks. This price escalation is not speculation; Japanese PC vendors like Sycom and TSUKUMO halted orders because DDR5 was four times more expensive than a year earlier.

The shortage is especially acute in high‑bandwidth memory. HBM packages are crucial for AI accelerators, enabling models to move large tensors quickly. Memory suppliers have shifted capacity away from DDR and GDDR to HBM, with analysts noting that data centers will consume up to 70 % of global memory supply in 2026. As a consequence, memory module availability for PCs and embedded systems has dwindled. This imbalance has even led to speculation that RAM could account for 10 % of the cost of consumer electronics and up to 30 % of smartphones.

In short, the present state of the compute crunch is defined by long lead times for data‑center GPUs, dramatic price increases for memory, and reallocation of supply to AI datacenters. It is also marked by the reality that new orders of GPUs and memory are limited to contracted volumes. This means that even companies willing to pay high prices cannot simply buy more GPUs; they must wait their turn. The shortage is therefore not just about affordability but also about accessibility.

Industry commentators have been candid about the severity of the shortage. BCD, a global hardware distributor, reports that data‑center GPU lead times have climbed to a year and warns that supply will remain tight through at least late 2026. Sourceability, a major component distributor, highlights that DRAM lead times have extended beyond twenty weeks and that memory vendors are implementing allocation‑only ordering, effectively rationing supply. Tom’s Hardware, reporting from Japan, notes that PC makers have temporarily stopped taking orders due to skyrocketing memory costs.

These sources paint a consistent picture: the shortage is not localized or transitory but structural and global. Even as new GPU architectures, such as Nvidia’s H200 and AMD’s MI300, begin shipping, the pace of demand outstrips supply. The result is a bifurcation of the market: hyperscalers with guaranteed contracts receive chips, while smaller companies and hobbyists are left to hunt on secondary markets or rent through cloud providers.

Understanding the shortage requires looking beyond the headlines to the underlying drivers. Demand is the most obvious factor. The rise of generative AI and large‑language models has led to exponential growth in token consumption. This surge translates directly into compute requirements. Training GPT‑class models requires hundreds of teraflops and petabytes of memory bandwidth, and inference at scale—serving billions of queries daily—adds further pressure. In 2023, early AI companies consumed a few hundred megawatts of compute; by 2026, analysts estimate that AI datacenters require tens of gigawatts of capacity.

Memory bottlenecks amplify the problem. High‑bandwidth memory such as HBM3 and HBM4 is produced by a handful of manufacturers. According to supply‑chain analysts, DRAM supply currently only supports about 15 gigawatts of AI infrastructure. That may sound like a lot, but when large models run across thousands of GPUs, this capacity is quickly exhausted. Furthermore, DRAM production is constrained by extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) and the need for advanced process nodes; building new EUV capacity takes years.

Advanced packaging constraints also limit GPU supply. Many AI accelerators rely on 2.5‑D integration, where memory stacks are mounted on silicon interposers. This process, often referred to as CoWoS, requires sophisticated packaging lines. BCD reports that packaging capacity is fully booked, and ramping new packaging lines is slower than adding wafer capacity. In the near term, this means that even if foundries produce enough compute dies, packaging them into finished products remains a choke point.

Prioritization by memory and GPU vendors plays a role as well. When demand exceeds supply, companies optimize for margin. Memory makers allocate more HBM to AI chips because they command higher prices than DDR modules. GPU vendors favor data‑center customers because a single rack of H100 cards, priced at around $25,000 per card, can generate over $400,000 in revenue. By contrast, consumer GPUs are less profitable and are therefore deprioritized.

Finally, the planned sunset of DDR4 contributes to the crunch. Manufacturers are shifting capacity from mature DDR4 lines to newer DDR5 and HBM lines. Sourceability warns that the end‑of‑life of DDR4 is squeezing supply, leading to shortages even in legacy platforms.

These root causes—insatiable AI demand, memory production bottlenecks, packaging constraints, and vendor prioritization—collectively create a system where supply cannot keep up with demand. The compute crunch is not due to any single failure; rather, it is an ecosystem‑wide mismatch between exponential growth and linear capacity expansion.

The compute crunch affects organizations differently depending on size, capital and strategy. Hyperscalers and well‑funded AI labs have secured multi‑year agreements with chip vendors. They typically purchase entire racks of GPUs—the price of an H100 rack can exceed $400,000—and invest heavily in bespoke infrastructure. In some cases, the total cost of ownership is even higher when factoring in networking, power and cooling. For these players, the compute crunch is a capital expenditure challenge; they must raise billions to maintain competitive training capacity.

Startups and smaller AI teams face a different reality. Because they lack negotiating power, they often cannot secure GPUs from vendors directly. Instead, they rent compute from cloud marketplaces. Cloud providers like AWS, Azure, and specialized platforms like Jarvislabs and Lambda Labs offer GPU instances for between $2.99 and $9.98 per hour. However, even these rentals are subject to availability; spot instances are frequently sold out, and on‑demand rates can spike due to demand surges. The compute crunch thus forces startups to optimize for cost efficiency, adopt smarter architectures, or partner with providers that guarantee capacity.

The shortage also changes product development timelines. Model training cycles that once took weeks now must be planned months ahead, because organizations need to book hardware well in advance. Delays in GPU delivery can postpone product launches or cause teams to settle for smaller models. Inference workloads—serving models in production—are less sensitive to training hardware but still require GPUs or specialized accelerators. A Futurum survey found that only 19 % of enterprises have training‑dominant workloads; the vast majority are inference‑heavy. This shift means companies are spending more on inference than training and thus need to allocate GPUs across both tasks.

One of the most misunderstood aspects of the compute crunch is the total cost of operating AI hardware. Jarvislabs analysts point out that buying an H100 card is just the beginning. Organizations must also invest in power distribution, high‑density cooling solutions, networking gear and facilities. Together, these systems can double or triple the cost of the hardware itself. When margins are thin, as is often the case for AI startups, renting may be more cost‑effective than purchasing.

Moreover, the shortage encourages a “GPU as oil” narrative—the idea that GPUs are scarce resources to be managed strategically. Just as oil companies diversify their suppliers and hedge against price swings, AI companies must treat compute as a portfolio. They cannot rely on a single cloud provider or hardware vendor; they must explore multiple sources, including multi‑cloud strategies, and design software that is portable across hardware architectures.

If scarcity is the new normal, the next question is how to operate effectively in a constrained environment. Organizations are responding with a combination of technical, strategic and operational innovations.

Because compute availability varies across regions and vendors, multi‑cloud strategies have become essential. KnubiSoft, a cloud‑infrastructure consultancy, emphasizes that companies should treat compute like financial assets. By spreading workloads across multiple clouds, organizations reduce dependence on any single provider, mitigate regional disruptions, and access spot capacity when it appears. This approach also helps with regulatory compliance: workloads can be placed in regions that meet data‑sovereignty requirements while failing over to other regions when capacity is constrained.

Implementing multi‑cloud is non‑trivial; it requires orchestration tools that can dispatch jobs to the right clusters, monitor performance and cost, and handle data synchronization. Clarifai’s compute‑orchestration layer provides a unified interface to schedule training and inference jobs across cloud providers and on‑prem clusters. By abstracting the differences between, say, Nvidia A100 instances on Azure and AMD MI300 instances on an on‑prem cluster, Clarifai allows engineers to focus on model development rather than infrastructure plumbing.

Beyond simple multi‑cloud deployment, companies need to orchestrate their compute resources intelligently. Compute orchestration platforms allocate jobs based on resource requirements, availability and cost. They can dynamically scale clusters, pause jobs during price spikes, and resume them when capacity is cheap.

Clarifai’s orchestration solution automatically chooses the most suitable hardware—GPUs for training, XPUs or CPUs for inference—while respecting user priorities and SLAs. It monitors queue lengths and server health to avoid idle resources and ensures that expensive GPUs are kept busy. Such orchestration is especially important when working with heterogeneous hardware, which we discuss further below.

For many organizations, inference workloads now dwarf training workloads. Serving a large language model in production may require thousands of GPUs if done naively. Model inference frameworks like Clarifai’s service handle batching, caching and auto‑scaling to reduce latency and cost. They reuse cached token sequences, group requests to improve GPU utilization, and spin up additional instances when traffic spikes.

Another strategy is to bring inference closer to users. Local runners and edge deployments allow models to run on devices or local servers, avoiding the need to send every request to a datacenter. Clarifai’s local runner enables companies to deploy models on resource‑constrained hardware, making it easier to serve models in privacy‑sensitive contexts or in regions with limited connectivity. Local inference also reduces reliance on scarce data‑center GPUs and can improve user experience by lowering latency.

The shortage of GPUs has catalyzed interest in alternative hardware. XPUs—a catchall term for TPUs, FPGAs, custom ASICs and other specialized processors—are drawing significant investment. A Futurum survey finds that enterprise spending on XPUs is projected to grow 22.1 % in 2026, outpacing growth in GPU spending. About 31 % of decision‑makers are evaluating Google’s TPUs and 26 % are evaluating AWS’s Trainium. Companies like Intel (with its Gaudi accelerators), Graphcore (with its IPU) and Cerebras (with its wafer‑scale engine) are also gaining traction.

Heterogeneous accelerators offer several benefits: they often deliver better performance per watt on specific tasks (e.g., matrix multiplication or convolution), and they diversify supply. FPGA accelerators using structured sparsity and low‑bit quantization can achieve a 1.36× improvement in throughput per token, while 4‑bit quantization and pruning reduce weight storage four‑fold and speed up inference by 1.29× to 1.71×. As XPUs become more mainstream, we expect software stacks to mature; Clarifai’s hardware‑abstraction layer already helps developers deploy the same model on GPUs, TPUs or FPGAs with minimal code changes.

In a world where hardware is scarce, GPU marketplaces and specialized cloud providers serve an important niche. Platforms like Jarvislabs and Lambda Labs allow companies to rent GPUs by the hour, often at lower rates than mainstream clouds. They aggregate unused capacity from data centers and resell it at market prices. This model is akin to ride‑sharing for compute. However, availability fluctuates; high demand can wipe out inventory quickly. Companies using such marketplaces must integrate them into their orchestration strategies to avoid job interruptions.

Finally, the compute crunch has spotlighted the importance of energy efficiency. Data centers not only consume GPUs but also vast amounts of electricity and water. To mitigate environmental impact and reduce operating costs, many providers are co‑locating with renewable energy sources, using natural gas for combined heat and power, and adopting advanced cooling techniques. Innovations like liquid immersion cooling and AI‑driven temperature optimization are becoming mainstream. These efforts not only reduce carbon footprints but also free up power for more GPUs—making energy efficiency an integral part of the hardware supply story.

When hardware is scarce, making each flop and byte count becomes critical. Over the past two years, researchers have poured energy into techniques that reduce model size, accelerate inference and preserve accuracy.

One of the most powerful techniques is quantization, which reduces the precision of model weights and activations. 4‑bit integer formats can cut the memory footprint of weights by 4×, while maintaining nearly the same accuracy when combined with calibration techniques. When paired with structured sparsity, where some weights are set to zero in a regular pattern, quantization can speed up matrix multiplication and reduce power consumption. Research combining N:M sparsity and 4‑bit quantization demonstrates a 1.71× matrix multiplication speedup and a 1.29× reduction in latency on FPGA accelerators.

These techniques are not limited to FPGAs; GPU‑based inference engines like NVIDIA TensorRT and AMD’s ROCm are increasingly adding support for mixed‑precision formats. Clarifai’s inference service incorporates quantization to shrink models and accelerate inference automatically, freeing up GPU capacity.

Another emerging trend is hardware–software co‑design. Rather than designing chips and algorithms separately, engineers co‑optimize models with the target hardware. Sparse and quantized models compiled for FPGAs can deliver a 1.36× improvement in throughput per token, because the FPGA can skip multiplications involving zeros. Dynamic zero‑skipping and reconfigurable data paths maximize hardware utilization.

Although training large models garners headlines, most real‑world AI spending is now on inference. This shift encourages developers to build models that run efficiently in production. Techniques such as Low‑Rank Adaptation (LoRA) and Adapter layers allow fine‑tuning large models without updating all parameters, reducing training and inference costs. Knowledge distillation, where a smaller student model learns from a large teacher model, creates compact models that perform competitively while requiring less hardware.

Clarifai’s inference service helps here by batching and caching tokens. Dynamic batching groups multiple requests to maximize GPU utilization; caching stores intermediate computations for repeated prompts, reducing recomputation. These optimizations can reduce the cost per token and alleviate pressure on GPUs.

While GPUs remain the workhorse of AI, the compute crunch has accelerated the rise of alternative accelerators. Enterprises are reevaluating their hardware stacks and increasingly adopting custom chips designed for specific workloads.

According to Futurum’s research, XPU spending will grow 22.1 % in 2026, outpacing growth in GPU spending. This category includes Google’s TPU, AWS’s Trainium, Intel’s Gaudi and Graphcore’s IPU. These accelerators typically feature matrix multiply units optimized for deep learning and can outperform general‑purpose GPUs on specific models. About 31 % of surveyed decision‑makers are actively evaluating TPUs and 26 % are evaluating Trainium. Early adopters report strong efficiency gains on tasks like transformer inference, with lower power consumption.

Reconfigurable devices like FPGAs are seeing a resurgence. Research shows that sparsity‑aware FPGA designs deliver a 1.36× improvement in throughput per token. FPGAs can implement dynamic zero‑skipping and custom arithmetic pipelines, making them ideal for highly sparse or quantized models. While they typically require specialized expertise, new software toolchains are simplifying their use.

The compute crunch is not confined to data centers; it is also shaping edge and consumer hardware. AI PCs with integrated neural processing units (NPUs) are beginning to ship from major laptop manufacturers. Smartphone system‑on‑chips now include dedicated AI cores. These devices allow some inference tasks to run locally, reducing reliance on cloud GPUs. As memory prices climb and cloud queues lengthen, local inference on NPUs may become more attractive.

Adopting diverse hardware raises the challenge of how to manage it. Software must dynamically decide whether to run on a GPU, TPU, FPGA or CPU, depending on cost, availability and performance. Clarifai’s hardware‑abstraction layer abstracts away the differences between devices, allowing developers to deploy a model across multiple hardware types with minimal changes. This portability is critical in a world where supply constraints might force a switch from one accelerator to another on short notice.

The compute crunch reverberates beyond the technology sector. Memory shortages are impacting automotive and consumer electronics industries, where memory modules now account for a larger share of the bill of materials. Analysts warn that smartphone shipments could dip by 5 % and PC shipments by 9 % in 2026 because high memory prices deter consumers. For automakers, memory constraints could delay infotainment and advanced driver‑assistance systems, influencing product timelines.

Different regions experience the shortage in distinct ways. In Japan, some PC vendors halted orders altogether due to four‑fold increases in DDR5 prices. In Europe, energy prices and regulatory hurdles complicate data‑center construction. The United States, China and the European Union have each launched multi‑billion‑dollar initiatives to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing. These programs aim to reduce reliance on foreign fabs and secure supply chains for strategic technologies.

Geopolitical tensions add another layer of complexity. Export controls on advanced chips restrict where hardware can be shipped, complicating supply for international buyers. Companies must navigate a web of regulations while still trying to procure scarce GPUs. This environment encourages collaboration with vendors who offer transparent supply chains and compliance support.

AI datacenters consume vast amounts of electricity and water. As more chips are deployed, the power footprint grows. To mitigate environmental impact and control costs, datacenter operators are co‑locating with renewable energy sources and improving cooling efficiency. Some projects integrate natural gas plants with data centers to recycle waste heat, while others explore hydro‑powered locations. Governments are imposing stricter regulations on energy use and emissions, forcing companies to consider sustainability in procurement decisions.

The market outlook is mixed. TrendForce researchers describe the reallocation of memory capacity toward AI datacenters as “permanent”. This means that even if new DDR and HBM capacity comes online, a significant share will remain tied to AI customers. Investors are channeling capital into memory fabs, advanced packaging facilities and new foundries rather than consumer products. Price volatility is likely; some analysts forecast that HBM prices may rise another 30 – 40 % in 2026. For buyers, this environment necessitates long‑term procurement planning and financial hedging.

While the current shortage is severe, the industry is taking steps to address it. New fabs in the United States, Europe and Asia are slated to ramp up by 2027–2028. Intel, TSMC, Samsung and Micron all have projects underway. These facilities will increase output of both compute dies and high‑bandwidth memory. However, supply‑chain experts caution that lead times will remain elevated through at least 2026. It simply takes time to build, equip and certify new fabs. Even once they come online, baseline pricing may stay high due to continued strong demand.

Analysts expect that HBM and DDR5 production will improve by late 2026 or early 2027. As supply increases, some price relief could occur. Yet because AI demand is also growing, supply expansion may only meet, rather than exceed, consumption. This dynamic suggests a prolonged equilibrium where prices remain above historical norms and allocation policies continue.

Looking ahead, XPU adoption is expected to accelerate. The spending gap between XPUs and GPUs is narrowing, and by 2027 XPUs may account for a larger share of AI hardware budgets. Innovations such as mixture‑of‑experts (MoE) architectures, which distribute computation across smaller sub‑models, and retrieval‑augmented generation (RAG), which reduces the need for storing all knowledge in model weights, will further lower compute requirements.

On the software side, new compilers and scheduling algorithms will optimize models across heterogeneous hardware. The goal is to run each part of the model on the most suitable processor, balancing speed and efficiency. Clarifai is investing in these areas through its hardware‑abstraction and orchestration layers, ensuring that developers can harness new hardware without rewriting code.

Regulators are beginning to scrutinize AI hardware supply chains. Environmental regulations around energy consumption and carbon emissions are tightening, and data‑sovereignty laws influence where data can be processed. These trends will shape datacenter locations and investment strategies. Companies may need to build smaller, regional clusters to comply with local laws, further spreading demand across multiple facilities.

Supply‑chain experts see early signs of stabilization around 2027 but caution that baseline pricing is unlikely to return to pre‑2024 levels. HBM pricing may continue to rise, and allocation rules will persist. Researchers stress that procurement teams must work closely with engineering to plan demand, diversify suppliers and optimize designs. Futurum analysts predict that XPUs will be the breakout story of 2026, shifting market attention away from GPUs and encouraging investment in new architectures. The consensus is that the compute crunch is a multi‑year phenomenon rather than a fleeting shortage.

The 2026 GPU shortage is not merely a supply hiccup; it signals a fundamental reordering of the AI hardware landscape. Lead times approaching a year for data‑center GPUs and memory consumption dominated by AI datacenters demonstrate that demand outstrips supply by design. This imbalance will not resolve quickly because DRAM and HBM capacity cannot be ramped overnight and new fabs take years to build.

For organizations building AI products in 2026, the imperative is to design for scarcity. That means adopting multi‑cloud and heterogeneous compute strategies to diversify risk; embracing model‑efficiency techniques such as quantization and pruning; and leveraging orchestration platforms, like Clarifai’s Compute Orchestration and Model Inference services, to run models on the most cost‑effective hardware. The rise of XPUs and custom ASICs will gradually redefine what “compute” means, while software innovations like MoE and RAG will make models leaner and more flexible.

Yet the market will remain turbulent. Memory pricing volatility, regulatory fragmentation and geopolitical tensions will keep supply uncertain. The winners will be those who build flexible architectures, optimize for efficiency, and treat compute not as a commodity to be taken for granted but as a scarce resource to be used wisely. In this new era, scarcity becomes a catalyst for innovation—a spur to invent better algorithms, design smarter hardware and rethink how and where we run AI models.

© 2026 Clarifai, Inc. Terms of Service Content TakedownPrivacy Policy